Mapping values for a value-based future in the Delta region

This article provides a glimpse into the content of the IDE MSc elective 'Design and the City' and shares the results for each project of the latest edition!

Over the past years, students in the course ID5127 Design & the City have explored the diverse roles design can play in enabling mission-driven innovation in cities.

Design plays a fundamental role in solving problems present in complex environments such as cities and enables sustainable social innovation. Cities serve as both problem domains and experimental grounds for tackling contemporary societal challenges, including environmental issues and climate change. The ways in which cities are utilized reflect the interests, aspirations, and visions of various stakeholders, essentially representing the values they uphold. However, within the complexity of urban contexts, identifying values and tensions among stakeholders is not always straightforward.

This year the students collaborated closely with the researchers of the Bauhaus of the Seas Sails project. The Bauhaus of Seas is an initial response to the New European Bauhaus challenge; it is a creative and interdisciplinary initiative aiming to reimagine sustainable living in Europe and beyond. Bauhaus of the seas refers to «marhaus» (literally «the sea as our home») or «baumar» («the sea as a space for creation and impact entrepreneurship»).

To walk the talk, Bauhaus of the Sea Sails envisages a continental mobilization across the primary and pivotal global natural domain: the sea. Within the Bauhaus of Seas context, cities close to the water will be offered solutions to achieve climate neutrality while doing design interventions within different regions and aquatic ecosystems: in Portugal (estuary), Italy (lagoon and gulf), Sweden (strait), Germany (river), and the Netherlands/Belgium (delta).

Throughout the course students deliver a Value Map that identifies the ecosystem of actors and communicates the value-driven pathways across multiple dimensions. The produced visual tools enable students to convey acquired insights. The purpose of a Value map is to articulate insights explicitly, revealing the conditions, values, and mindset within the port city.

The value maps of this year’s students are part of PortCityFutures’ virtual exhibition, or can be found below.

The value of Rotterdam and its rainwater

Jos van der Velden – Karel Hamburg – Maarten de Jong

Value map

Jos van der Velden, Karel Hamburg and Maarten de Jong elaborated upon the vision of the BoSS consortium for a sustainable, inclusive, and beautiful future in the face of the climate crisis, and have undertaken a comprehensive exploration of Rotterdam, a city known for innovation and diversity. Their process guided by the New European Bauhaus values of beauty, sustainability, and togetherness informed the creation of an actionable value map.

The map divides Rotterdam in five areas, identified by the municipality itself: North (Noord), South (Zuid), central (centrum), West, and East (Oost). The borders of the areas refer to borders defined by the Municipality of Rotterdam (fig.1).

Figure 1.

The use of the map follows three steps. The first one is an overall introduction to the city, to the BoSS and to the scope of the map. Then in the second step, by clicking on the specific areas the values and challenges of each one of them are shown (fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Figure 2.

During the analysis of the city and its initiatives, they particularly focused on the Heliport project in Rotterdam North. Here rainwater is used as a key element for a children’s playground to raise awareness on its usage. Therefore, in step three, the map particularly focuses on the relationship between the city, its citizens and the usage of rainwater. In particular, they used Behavior Change Communication (BCC) model (Wagle, 2019), to develop a six-level framework for understanding behavioral change in rainwater management in each area of Rotterdam (fig.3). In this step of the map, by clicking on each area, it is possible to see in which stage it has been ranked to help identify suitable projects that align with the region’s stage of change (fig.4).

Figures 3, 4.

Figures 3, 4.

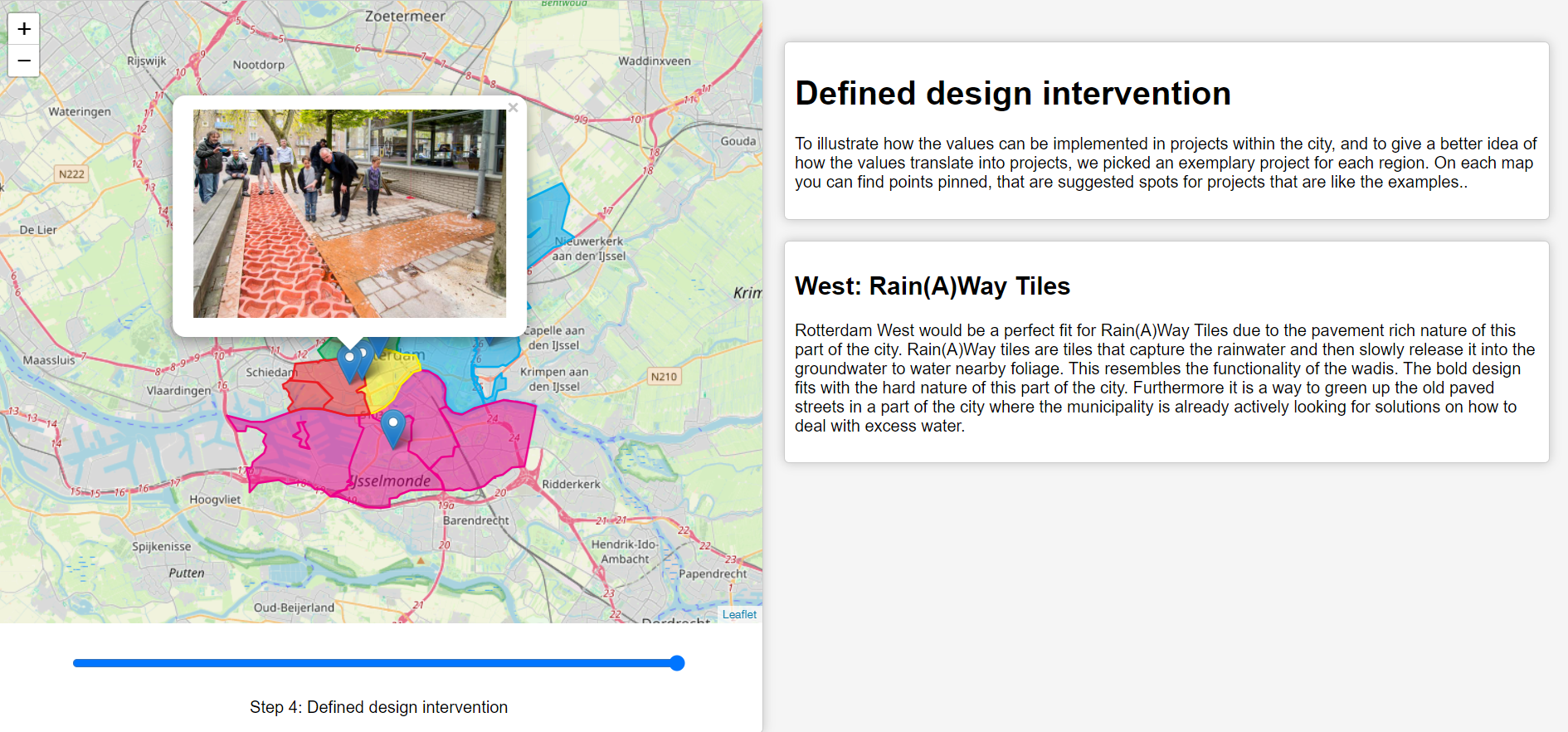

Finally, in step four, initiatives related to the usage of rainwater are shown to illustrate how the values can be implemented in projects within the city, and to give a better idea of how the values translate into projects (fig.5).

Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The Value map provides the reader with some useful insights into the following aspects:

- Values and design possibilities

The value map offers insight into the unique values and characteristics of various regions within Rotterdam, aiding the design of future projects. It serves as a resource for newcomers to the city, enabling them to tailor solutions to the specific culture of each area. - Regional Diversity

In the map, one specific port city is being discussed, however the values and hence the type of suitable designs for each region of the city differs greatly. The map highlights the significant differences in values and suitable design approaches across Rotterdam’s various regions, emphasizing the need to understand local values for project success. While applicable to similar cities, it should be seen as a guideline, not a direct template. - Inspiration for future projects

The value map showcases existing projects and their contexts, providing examples of how to enhance the relationship between port cities and water. It serves as a source of inspiration for future initiatives focused on sustainability, inclusion, and beauty in coastal areas.

In summary, the exploration and mapping of Rotterdam lay a foundation for informing new initiatives while offering a blueprint for other regions facing similar challenges.

Navigating the Green Dilemma: Understanding Stakeholder Values in the Borssele Wind Park

Ivy Steijn – Laura van der Linden – Nora Allan – Sanne Grommer

Value map

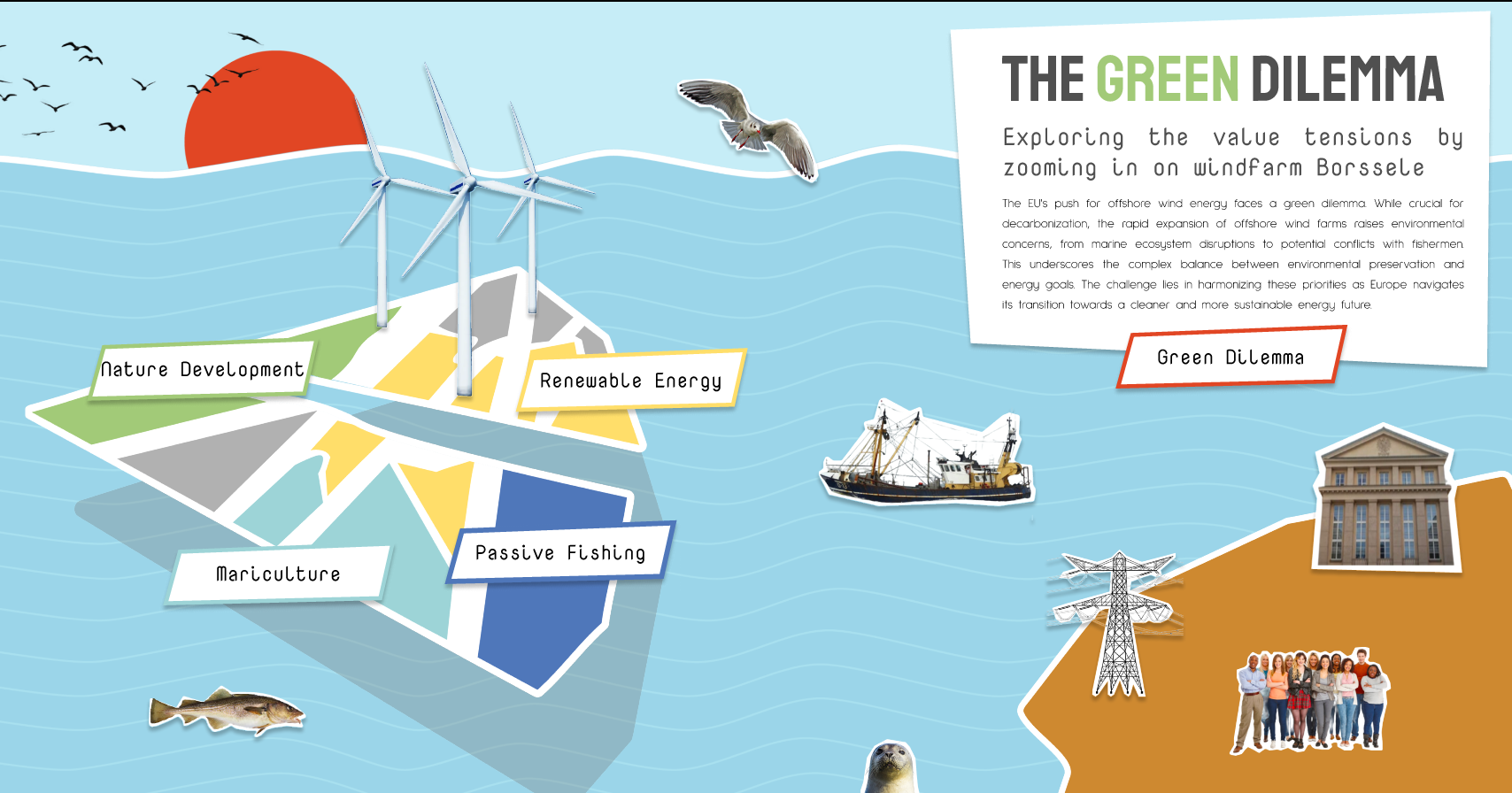

In a world facing the urgent need for sustainable energy solutions, the Netherlands has found itself at the center of a ‘Green Dilemma’. The construction of wind parks along the Dutch coastline, accelerated by efforts to combat global warming, has raised questions about their impact. This is because the Green Dilemma involves a complex web of stakeholders, each with their own interests and values.

The Borssele offshore wind energy area, located in the North Sea, serves as a crucial case study. It is the first of its kind, exploring the concept of shared space utilisation, where initiatives within mariculture, nature development, passive fishing, and renewable energy coexist in the wind park. For example, initiatives such as growing seaweed have sparked the interest of energy providers as a possible future energy source, indicating the potential for shared value.

The contribution of the value map lies in its ability to illustrate the interests, value alignments,and value tensions among diverse stakeholders in the Borssele wind park. It provides a visual representation of the complexities associated with the wind park, showing us that it is not a one-size-fits-all solution.

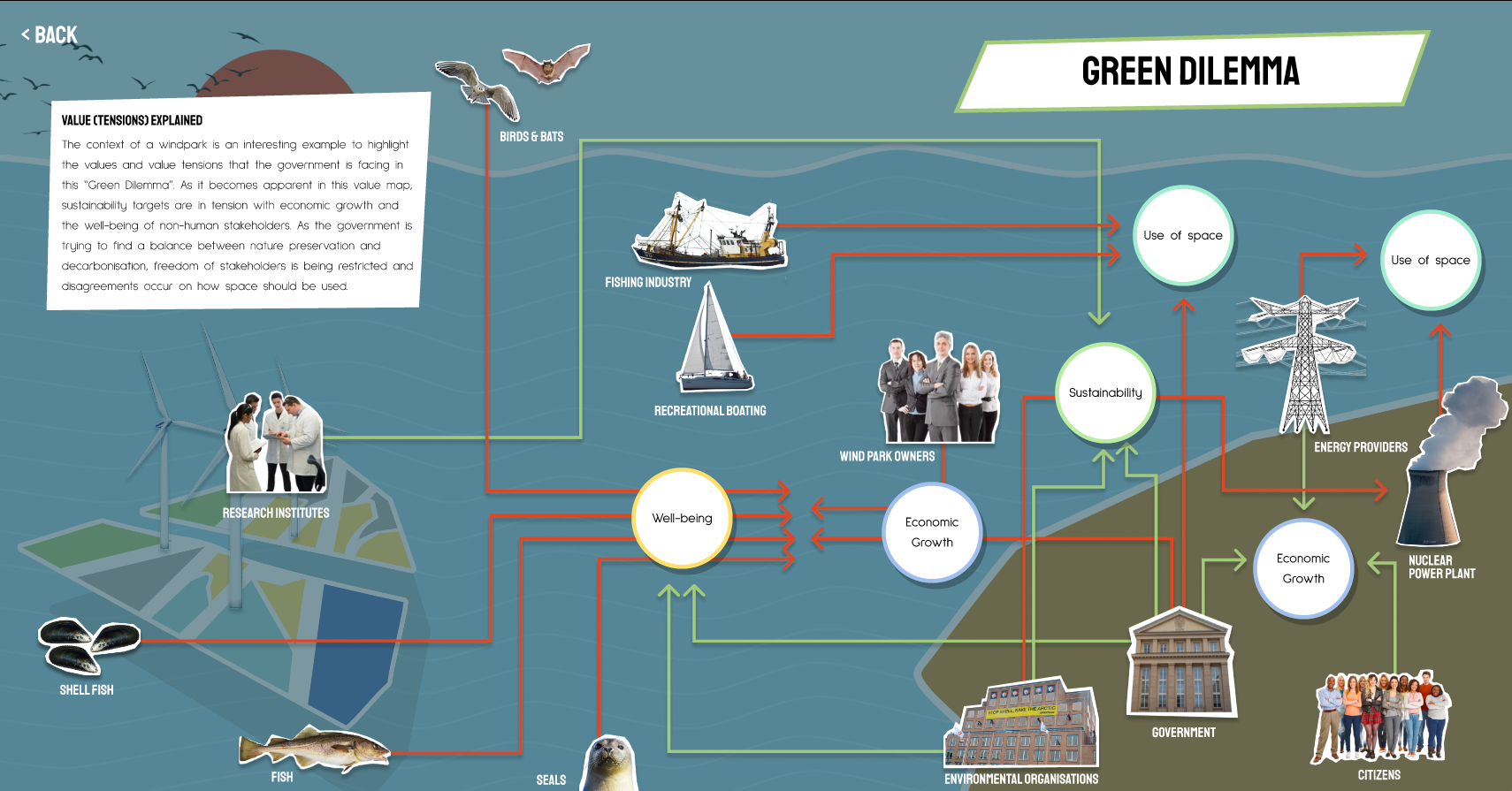

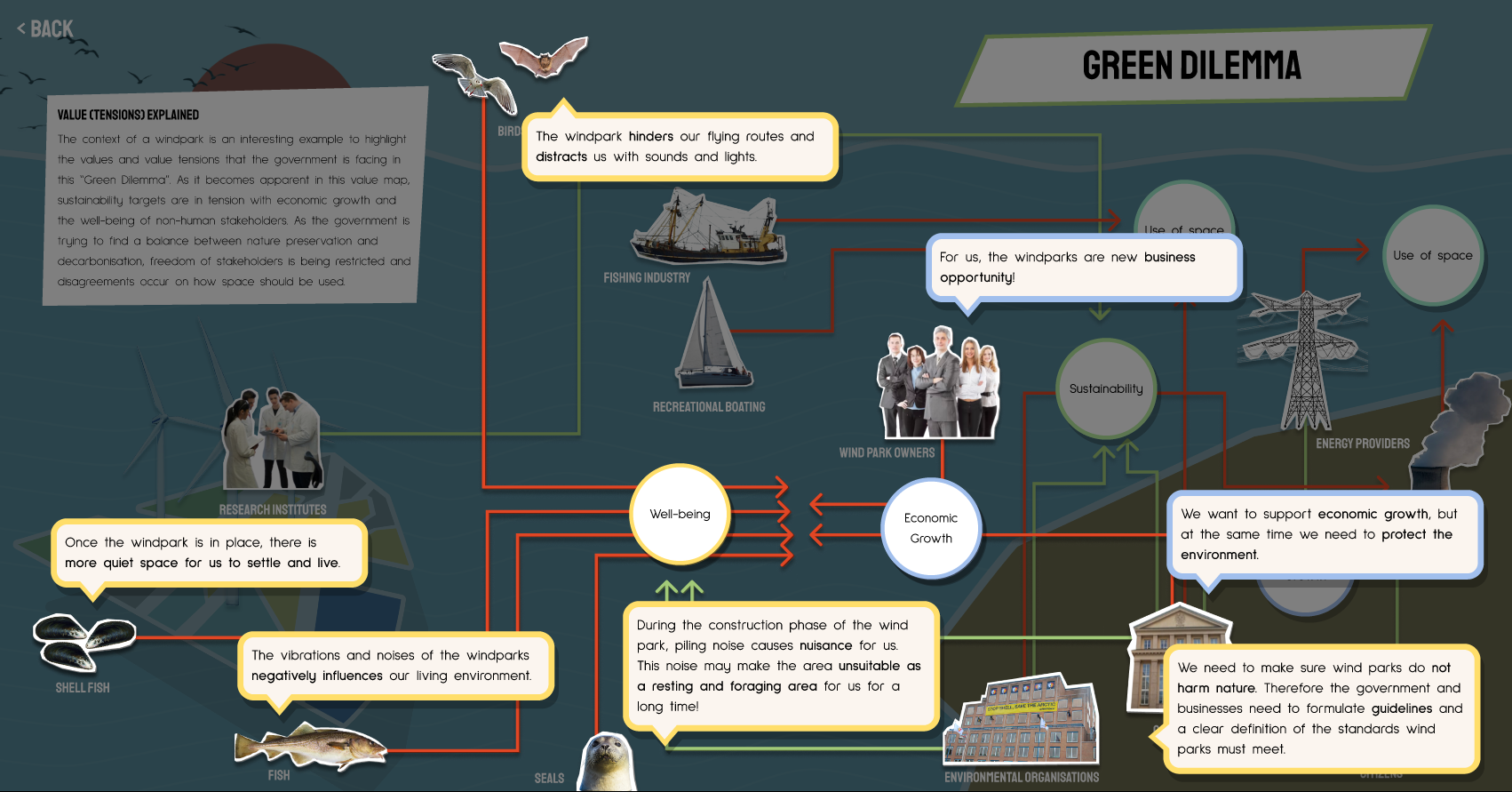

The map visually synthesizes the green dilemma, using the context of the Wind Park Borssele (fig. 6). By clicking on the Green Dilemma box, the different stakeholders are shown with their related values and their tensions in a map (fig. 7). By hovering on the different elements, more information is given (fig. 8).

Figure 6.

Figure 7.

Figure 8.

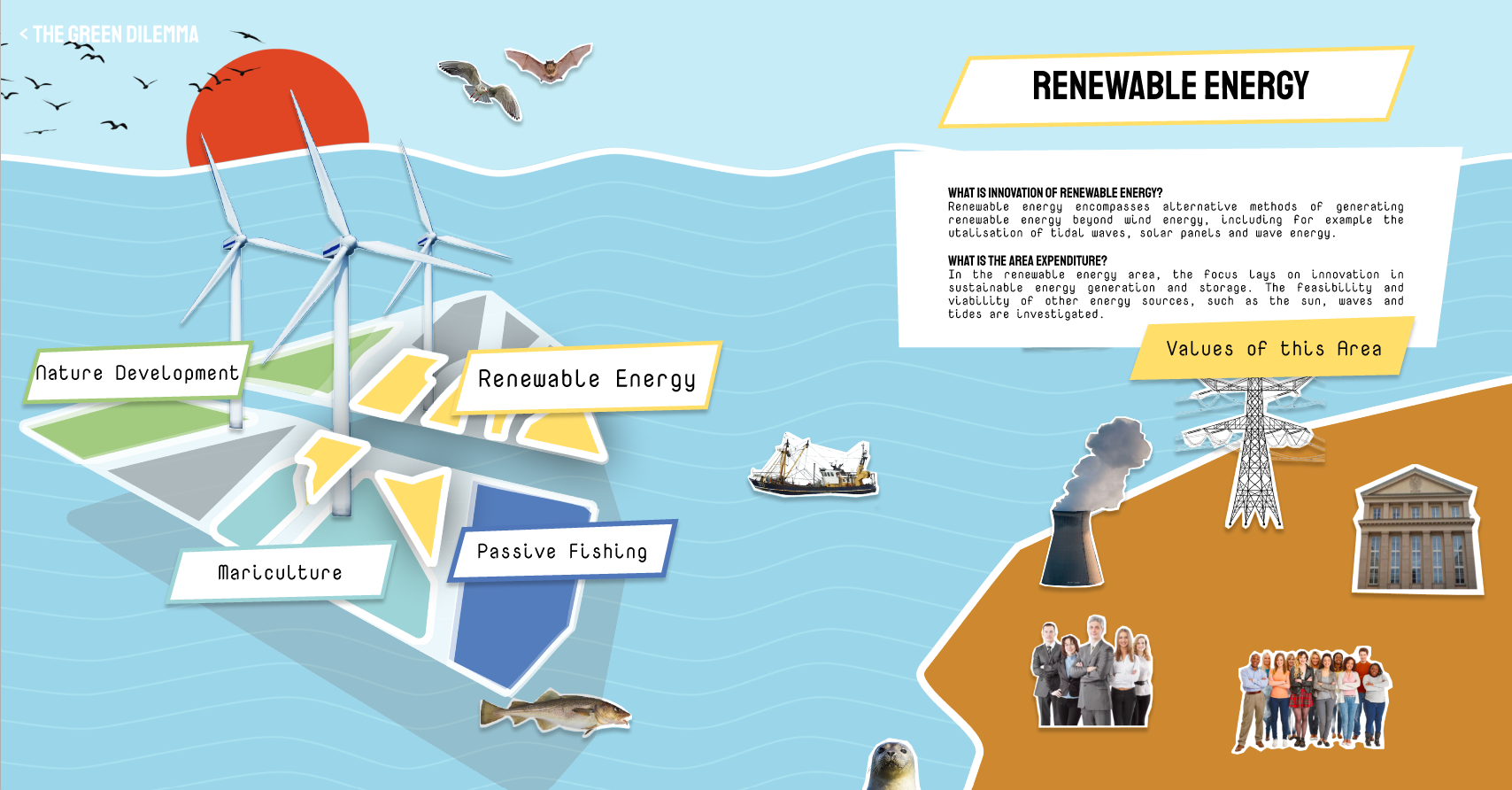

Going back to the initial view of the map (fig. 6), the representation of the wind park is divided into four areas: Nature Development, Renewable energy, Mariculture, Passive fishing. By selecting each one of them a description is given (fig. 9) and by continuing to the “values of this area” another visual mapping stakeholders of the specific area appears (fig. 10). With the same hovering mechanism, other values and tensions are explained.

Figure 9.

Figure 10.

The map of wind park Borssele can be used to formulate value-driven transitions that consider the interests of all stakeholders. By studying the value map, impact makers, such as designers, citizens or governmental institutions, can comprehend the diverse interests of the various stakeholders, along with how these values can either align or create tension with one another. This would facilitate the formulation of value-driven transitions that balance environmental preservation, economic growth, and societal well-being. Consequently, the value map becomes a tool for shaping a more sustainable future that respects the values and interests of both human and non-human actors.

The Borssele wind park is an intriguing case study that serves as an element of the larger global effort to transition to sustainable energy sources. As we navigate this Green Dilemma, the value map offers a roadmap towards finding that optimal balance that benefits all stakeholders involved. It is giving a voice to all human- and non-human actors. Furthermore, it is important to understand the values of all stakeholders and how their interests interact to solve the Green Dilemma and build a more balanced future. The value map of wind park Borssele is a valuable resource in this dilemma, shedding light on a complex issue that has far-reaching implications for energy transitions worldwide.

Blue Values: Rotterdam’s Blue-Economy Landscape

Lori Lo – Rijk Roozenbeek – Siqi Chen

This value map stems from analyzing the relations between stakeholders, value flow, value contribution and future possibilities based on an existing project Alga.farm, based in Rotterdam, in the Delta region. Alga.farm is the pilot project selected by Lori Lo, Rijk Roozenbeek and Siqi Chen, and it consists in the use of the spaces of the former Tropicana swimming pool to grow fresh spirulina. The entire process, based on the pilot project, involves discussing the opportunities of plant use and plant-based products initially. However, through the analysis of this project, it became evident how plants are not the only important factor, but more important elements align with the environment and the stakeholders. For instance, the maker spaces become the medium bridging abandoned areas and innovative initiatives, in this case they become revitalized by being used to grow the algae. This showed a deeper and wider understanding of the interconnections between sea life, the environment, and the city.

After delving deeper into the topic through various means, the project impact was classified into three scales (Drop-pilot scale/Ripple-city scale/Wave-wider scale). Subsequently, related cases from different aspects were individuated and the overall values that connect the city and its maritime environment have been defined, together with the value flow toward stakeholders.

The value map goal is to create an overview of the complex network inherent in a circular economy, where numerous connections are required. The value map visualizes and reflects the scope of the focused area, the types of projects, the value classifications (including the flow between different parties and stakeholders) and the timeline from the past to the future. Regarding the wider effects of locally grown algae itself, it creates opportunities to utilize the plant for production, including materials, healthy food, and nature regeneration. Additionally, it helps raise citizens’ awareness and prompts action. Simultaneously, residents can be made aware of how useful algae is when applied in different industries.

Moreover, by integrating a few associated projects related to the pilot project, the map shows the great potential of collaboration, involving both companies and citizens. These efforts are accelerated by governmental support and willingness on investment for such projects. Following this line of thinking, these project initiatives originally focused on presenting more sustainable technologies, which can be perceived as oriented toward a green economy. After the analysis and detailed assessment, a shift from the green economy toward the blue economy in different industries was highlighted. Common projects involve using algae for oxygen production or as an excellent protein source, aligning with sustainability goals on the green economy side. However, other projects, such as the Algae facade, aim to use fast-growing algae to generate materials for building panels, providing both heat energy and sun protection. This signifies the importance of initially caring for our environment and subsequently integrating economic aspects, symbiotically interacting with the environment in the process.

To conclude, the pilot project and other related projects are used in the map to trigger a different way of thinking of sea life, plant use, and the relations of buildings in the city (e.g., the maker-space as a medium and the abandoned places being reused).

The importance of reaching the sustainability goals, creating a green economy, is undeniable. However, the more ultimate goal is to create a harmonized living area, suitable for all creatures’ symbiosis with the environment by implementing the blue economy ideas.

Elevating Rotterdam: Value Mapping the Bottom-Up Initiative Rotterdam Rooftop Days

Ömer Taha Döver – Nicole Marques Morgado – Silke Rijcks

Value map

This map represents the values of the initiative Rotterdam Rooftop Days (Rotterdamse Dakendagen in Dutch). In this now yearly recurring event that takes place within the port city of Rotterdam, visitors were allowed to travel through all kinds of innovative interventions on how rooftops are used now or how they could be used in the future. Temporary installations were built on top of a variety of rooftops of the city to highlight the vast amount of unused space. The main goal of this initiative is to increase awareness of the potential of rooftop spaces, which could serve as a ‘second layer’ to create more liveable, biodiverse, sustainable, and healthy cities. Therefore, it can help to tackle major challenges like climate change, the housing crisis, and the transition to renewable energy (MVRDV, n.d.-b).

The Bauhaus of the Seas Sails project encourages designers to shift to designing complex interactions that bring about a critical awareness of modern-day practice and future possibilities (Bauhaus of Seas, 2023). This aligns neatly with the Rotterdam Rooftop Days, as the organisation wants to open up debate and present innovative possibilities. Artists, designers, and architects were involved in creating the exhibition and made professional city makers (real estate owners, developers, policymakers, etc.) aware of the possibilities of rooftops. Showing what is possible and raising awareness was positioned as the first step toward reinforcing behaviour and putting the roofs into use.

The Value Map is customised to the specific context of its main focus, the port city of Rotterdam. It showcases the stages ‘before’, ‘during’, and ‘future’ of the Rotterdam Rooftop Days initiative. The temporal nature of this initiative was one of the factors in choosing it as the focal point of the Value Map, as it highlights a direction for design that goes beyond solution-based and explores other roles, such as critique and raising awareness.

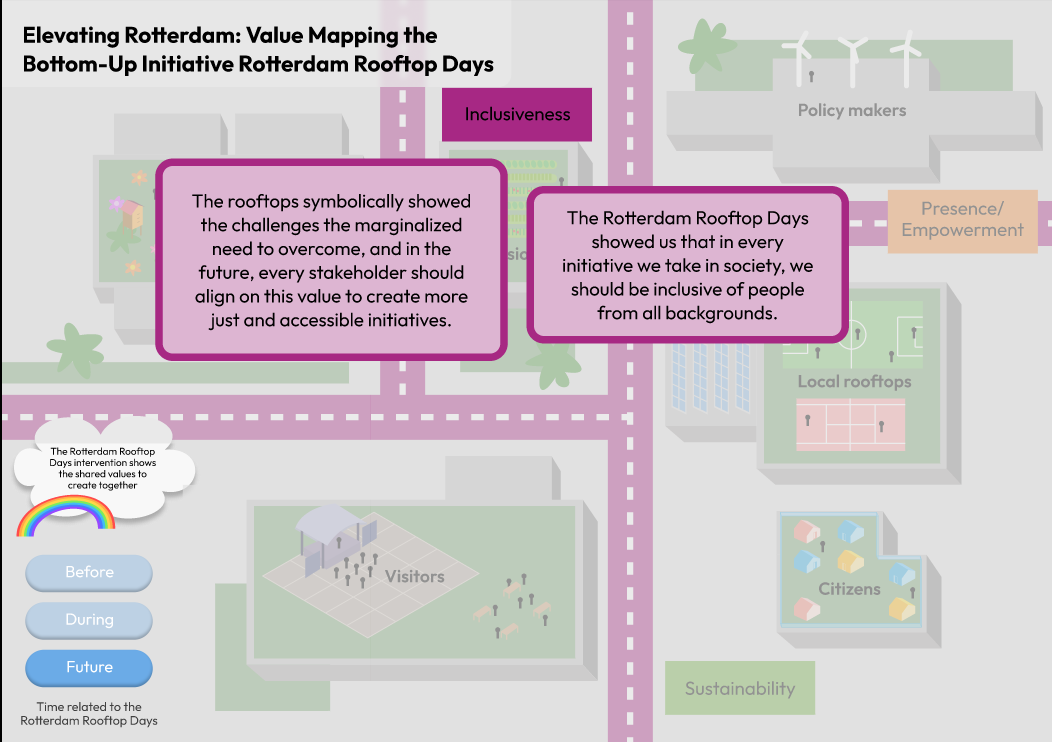

Before

The ‘before’ phase of the Value Map, seen in Figure 11, shows a spectrum of actors, from policymakers to residents, all influencing the dynamics of the city but not working cohesively. The rooftops, as depicted in the ‘before’ phase, remain unused and empty, a striking symbol of wasted space and untapped potential. The rendering in shades of grey visible in Figure 11 serves as a grim reminder of the under-utilisation of this urban canvas.

Figure 11.

During

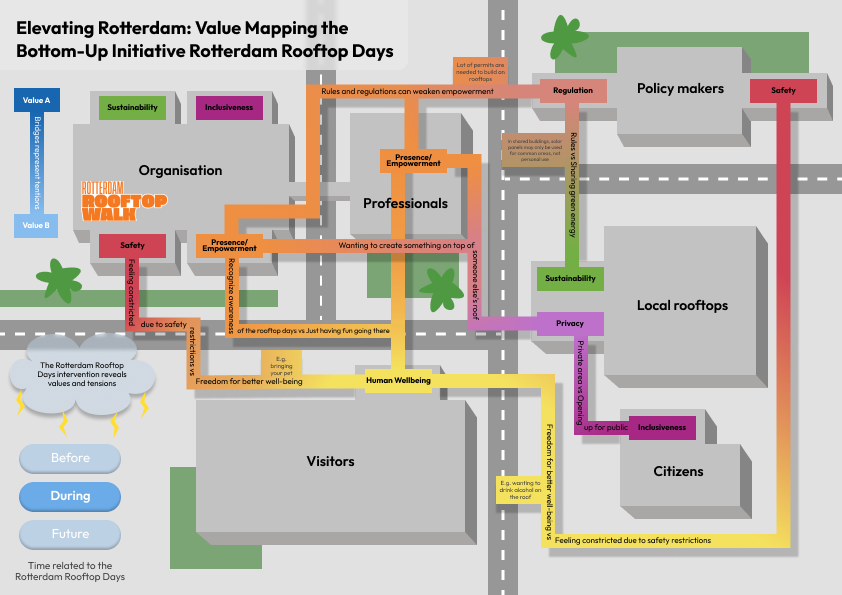

The ‘during’ phase of Rotterdam’s Rooftop Days showcases the transformative impact of key values such as Sustainability, Inclusiveness, Presence/Empowerment, Safety, Human Well-being, Privacy, and Regulation on stakeholders and the urban landscape. The vibrant use of colours highlights the trade-offs and conflicts inherent in value-driven transitions, resembling the vibrant nature of the initiative (fig. 12).

Figure 12.

Future

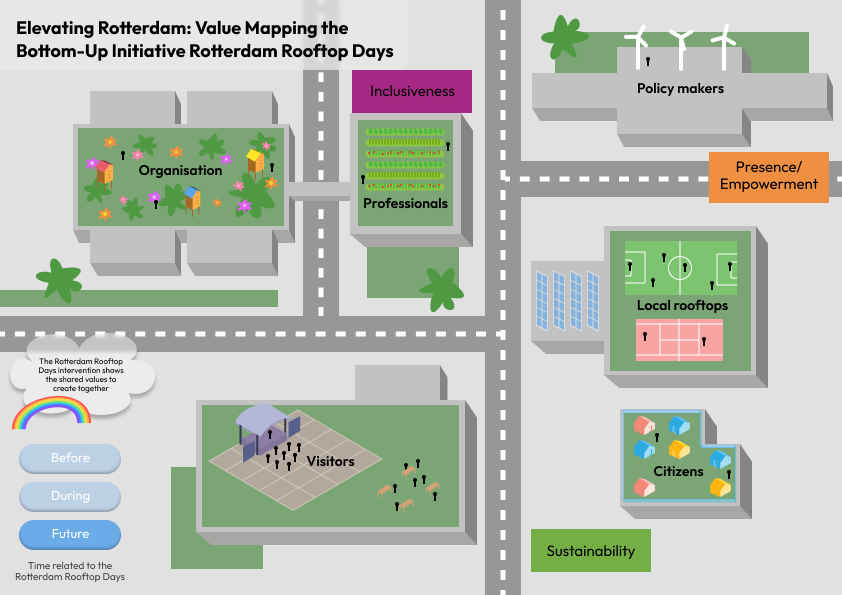

The ‘future’ phase, as seen in Figure 13, reflects the shared vision and commitment of stakeholders to work toward a better, more sustainable, inclusive, and empowered urban environment. The emphasised values of Sustainability, Inclusiveness, and Presence/Power capture the essence of the collective vision for the ‘future’. By clicking on these values more information are given (fig. 14).

These choices, inspired by The Rotterdam Rooftop Days, highlight the importance of aligning stakeholders with these values to create lasting and positive change in port cities.

Figure 13.

Figure 14.

Figure 14.

The role of design in mission-driven innovation was examined through the professional practices of expert designers in the Rotterdam Rooftop Days as a discrete organisation, as well as the diffuse design skills and mindset of other collaborators, including visitors. This spectrum of design capabilities made the many layers, classifications, and embodiments design can take on in urban innovation further clear. The stakeholder mappings made this more explicit while simultaneously highlighting the significance of various ways of designing together (co-design, participatory design, etc.).

The initiative and its material embodiment in the form of temporary rooftop structures can be likened to a symbolic representation of how design can go beyond solutionism and take on new roles. The structures do not serve any intrinsic purpose in the city context; they are temporary and meant to be taken down, yet, they posit a reference point to initiate dialogue and criticism. It appears that design can also be positioned as a catalyst for change rather than create the change itself.

Water quality of the Meuse

Florence Kao – Shervin Tjon – Federico Villa

The River Meuse, also known as the Maas, is a major European river that flows through France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. The Meuse plays a crucial role in transportation, agriculture, and tourism throughout its course, contributing to economic development. The river faces water quality issues due to pollution from industrial discharges and agricultural run-off, prompting countries like the Netherlands to address and improve water quality through regulations and conservation initiatives.

Currently, several projects are and have been designed to improve the situation of the River Meuse. Various actors are involved in projects: government, NGOs, community Education, the association of water companies, research institutes, communities, and citizens.

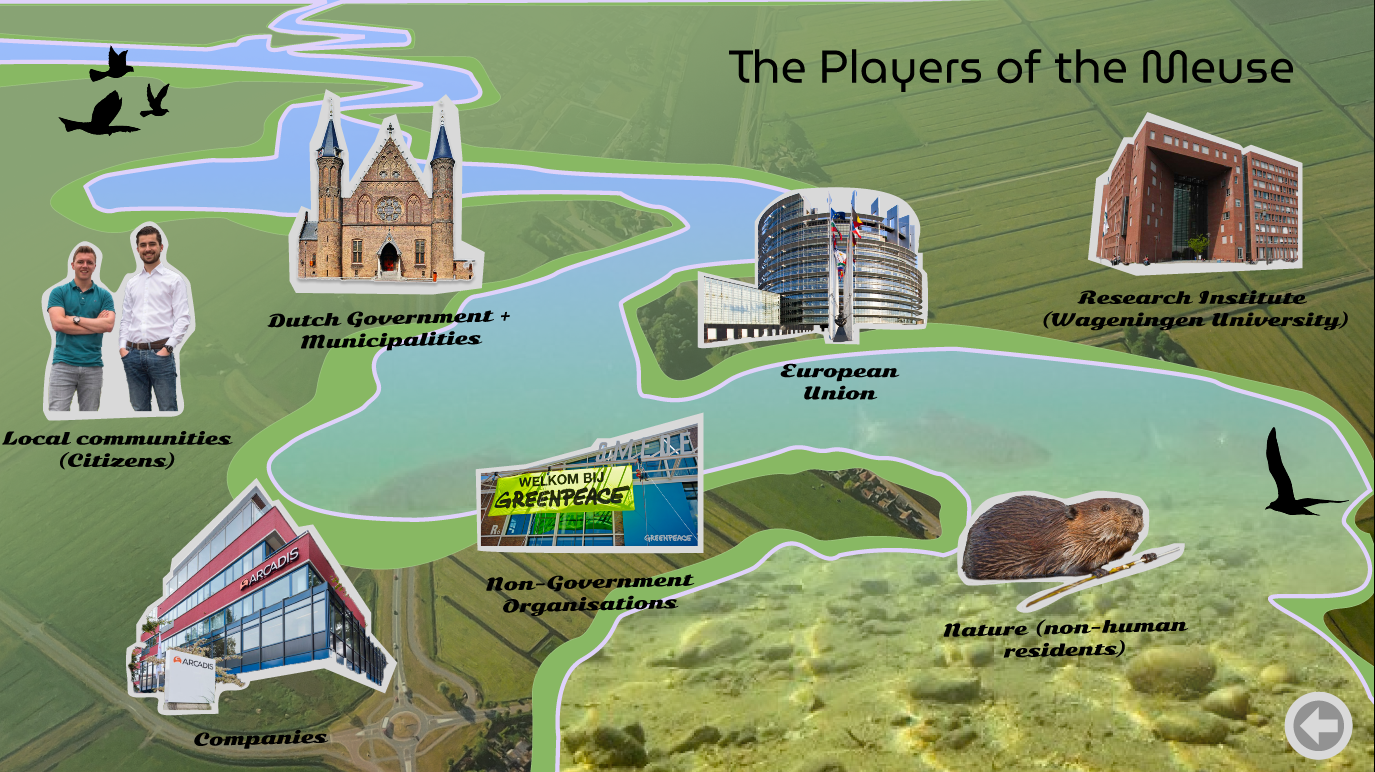

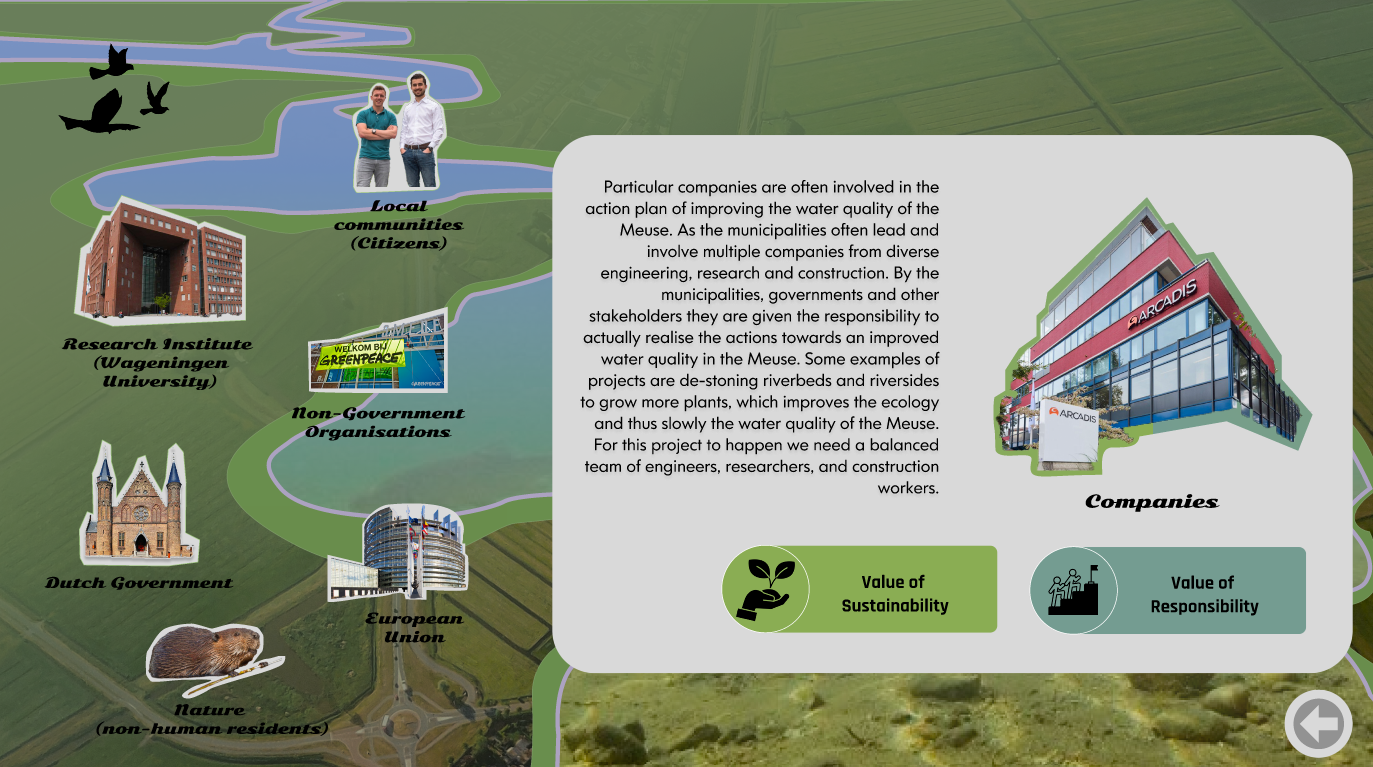

The value map looks into this context through three different sections (fig. 15). “The players of the Meuse” which involves the stakeholders where each illuminate the values and interplay of interests among the participants engaged in the upkeep and enhancement of the Maas River (fig. 16). Further explanations can be shown when clicking on the values of the stakeholders (fig. 17).

Figure 15.

Figure 16.

Figure 16.

Figure 17.

Figure 17.

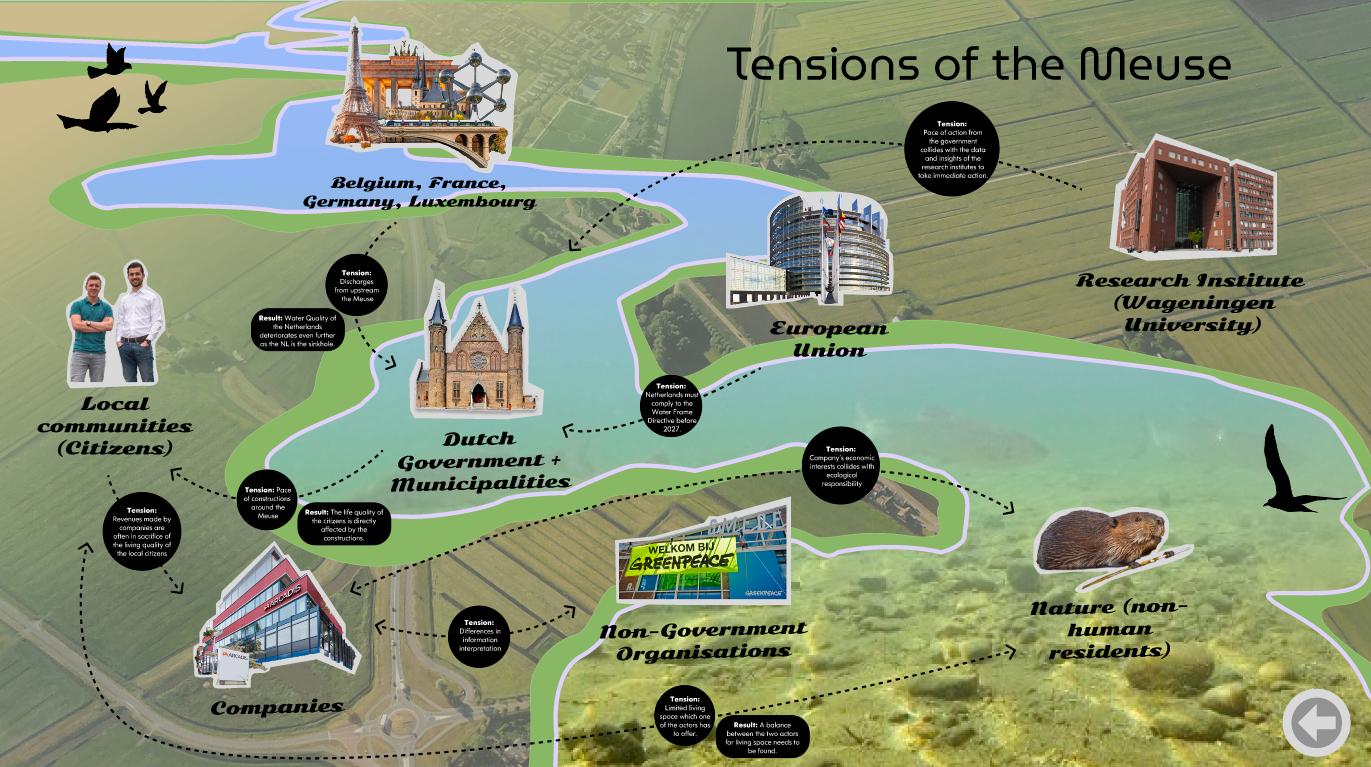

Secondly, the “Tensions of the Meuse” (fig. 18) shows the main tensions between the stakeholders who are involved in improving the water quality of the Meuse, with conflicts arising from the trade-off between revenue, sustainability, and quality of life.

Figure 18.

Figure 18.

Finally the Designer’s role in order to improver the water quality of the Meuse (fig. 19). Figure 19.

Figure 19.

Many stakeholders may not fully grasp their potential within this context. With the aid of this value map, all involved parties can unveil their roles and actively contribute to the formulation of fresh prospectives

To help this process and to align different stakeholders Florence Kao, Shervin Tjon, Federico Villa identified three core values followed by related challenges that should be the focal point for Meuse in the future:

- Design for ecology with an emphasis on enhancing water quality

Shaping a sustainable future requires stakeholders to adopt a “Design for Ecology” mindset. The government and NGOs should promote collaborative discussions on the topic.

However, climate change is creating pressure on government authorities to accelerate sustainability efforts while economic sectors may require time to transition to eco-friendly practices. - Design for shared responsibility

The Meuse River system requires shared responsibility for its long-term well-being. Pollution necessitates a shift towards stewardship, with stakeholders recognizing their responsibility to preserve the river.

However, research indicates that people are more willing to take environmental responsibility when they perceive the problem as real and the solutions as practical and effective. - Design for crystal clear waters and information

Transparency and information clarity are crucial for sustainable Meuse River management. An open platform is needed to reveal data sources and motivations, encourage real-time data contributions, and evolve to offer deeper insights.

However, effective information management requires advanced technology, operational stability, expert curation, and transparency for effective water quality management, to facilitate informed decision-making and accessibility for stakeholders.

The mentioned challenges make the individuated value hard to translate innovative pockets into actual sustainable practices, with the collaboration and consensus among diverse stakeholders. Here the designer can play an important role in value transition:

- Facilitator (Design for ecology – enhancing water quality)

Designers can facilitate stakeholder discussions, balancing ecological preservation and economic activities, using user insights to ensure solutions align with local values and capacities. - Strategist (Design for shared responsibility)

Designers can function as strategists who create sustainable, feasible, and optimistic strategies by utilizing user insights to effectively communicate the benefits of shared responsibility to various stakeholders. - Communicator, mediator (across all values)

Designers can effectively communicate, bridging the gap between niche innovations and regime acceptance, and facilitating collaborative discussions to help stakeholders find common ground and address potential tensions.

Industry vs Nature in the Maasvlakte and National Reserve

Teun van Woudenberg – Andrija Stanković – Thomas van der Helm

This map (fig.20) elaborates on the disconnection between nature and industry in the locations of the Maasvlakte and National Reserve Biesbosch. The industry at the Maasvlakte is emitting vast quantities of carbon dioxide, while nature is not able to absorb this amount of carbon dioxide. The nature at the Biesbosch is also not able to absorb the amount of carbon dioxide that is released from the chemical companies that lay in proximity to this nature reserve.

The value map is a visual representation of the tensions between nature and industry in the selected areas. It is designed to engage viewers, enabling them to analyse data and form their own conclusions. The value map is intended to be a versatile tool that encourages data-driven storytelling and supports informed discussions. This data driven approach creates awareness of the values at stake in the relationship between nature and industry in port cities.

The specific locations of the Maasvlakte and National Nature Reserve Biesbosch derived from research that brought to identify different tensions in the area of the Delta that has an influence in and around the port city of Rotterdam.

In the ever-changing landscape where industry and nature come together, Maasvlakte in Rotterdam and National Park De Biesbosch serve as clear examples. Maasvlakte represents human innovation and growth, a busy center of trade that blends with its natural environment, while De Biesbosch, a place of natural beauty, lives alongside some industrial areas.

The value map (fig.20) shows the two selected areas by highlighting in the first place the relationship between CO2 emissions and its absorption. This reveals the balance and conflicting interests between industry and nature, that are better explained in the central part of the map.

Firstly, companies want to maintain a sustainable business and be viable, while sustainability for nature has another meaning, focusing more on ecology and biodiversity. Also, other conflicting values are generated by industries not being transparent about their actions and the lack of responsibility for nature. The tensions are highlighted with red connecting lines in the value map.

Figure 20.

There is a strong unbalance between nature and industry. The amount of pollution outweighs the amount of absorption by a large factor. It is important to have conversations about the polluting effect that industry has on nature. This creates awareness of the tension by addressing it and by letting the viewer form its own opinion on the topic.

Nature and industry in proximity to each other creates tensions between their values. It is important to understand these values for nature and industry in order to let them coexist next to each other. This data driven value map gives the viewer the information to create their own narrative in the tension between nature and industry. These different narratives are the starting point for conversations about the unbalance of nature and industry and creates awareness for the clashing values that nature and industry have in port cities.

The goal of the map is to inspire to chart a path where both (nature and industry) can coexist and contribute to a sustainable future.